Embracing Vintage Techniques for Natural Scented Soap

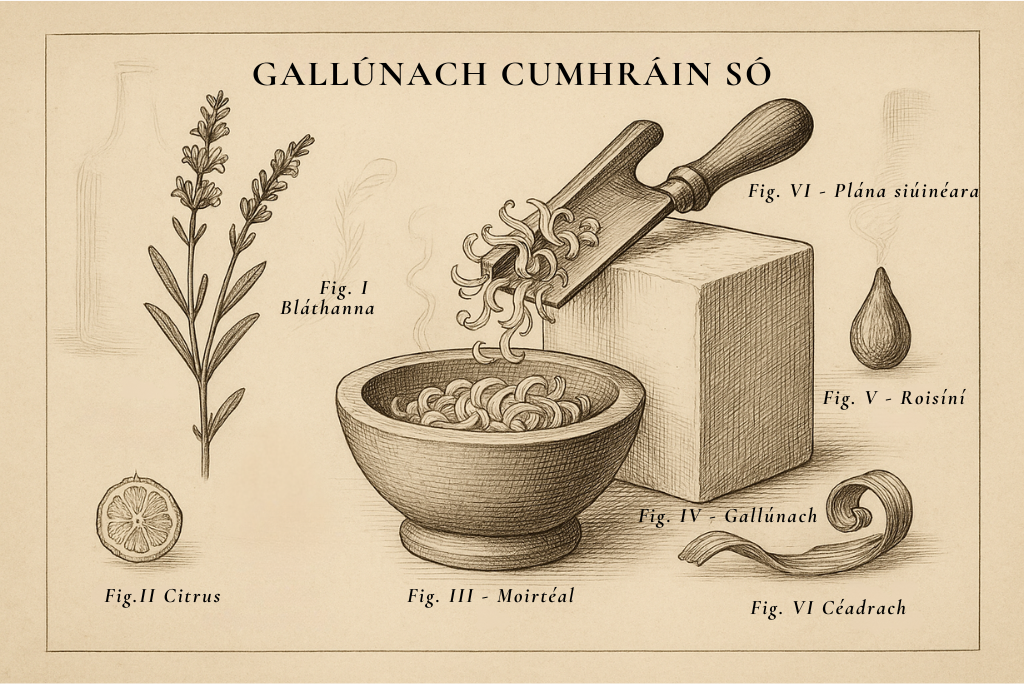

By avoiding heat at the perfume stage, we kept every nuance of your natural essential oils intact. We also used mechanical methods – grinding, extruding, pressing – just as was done on a larger scale with classic equipment. (In Piesse’s time, a simple setup with a plane, mortar, and hand-press was “exceedingly convenient and economical” for small batches.) With some creativity, those vintage methods can be adapted to a home workshop or lab.

To recap the benefits of this process:

Preserved Fragrance: Delicate top notes and natural essences aren’t lost to heat. The soap smells true to the original oils, especially at first use when the burst of top notes is strongest.

Rich, Complex Scent: You can incorporate essential oil blends that would be impossible in hot-process soap (because they’d flash off). Think of real jasmine, citrus, neroli, etc. – they’ll smell brighter. If you included base notes, you have a full spectrum of aroma that lingers on the skin.

Smooth, Dense Texture: The act of milling and pressing tends to create a very smooth, hard bar. Your soaps will likely be denser and longer-lasting in the bath than a regular cold-process bar. This is why commercial “triple-milled” soaps are prized – you’ve effectively done a similar thing. By shaving and recombining, you’ve removed excess air and created a tight matrix. (Historically, the soap “flakes or ribbons” from the mill were pressed into one solid mass and moulded. We achieved that with our grinding and hand-pressing.)

All-Natural & Custom: Perhaps best of all, your soap contains only natural ingredients – no synthetic fragrances, just the essential oils you chose. And you have complete control over the scent blend. This is a truly artisanal product, made with a nod to traditional perfumery and soapmaking knowledge.

In summary, to create highly scented natural soaps without using heat – you just need to employ mechanical techniques instead. By using a food processor (or mortar and pestle) to finely pulverise the soap, then blending in essential oils while cool, and finally extruding/pressing into shape, you’ve replicated on a small scale what the big soap factories do with huge machines. The result is a “perfumed soap” in the truest sense. This approach was well documented in older soap-making texts and you’ve improved on the common internet recipes by going back to those roots and equipment. Enjoy your uniquely crafted soap – when you lather up, those top-note essences should bloom beautifully, “making luxury naturally perfumed soaps for top notes, baby!” 😄

Remember that a century-and-a-half ago, a perfumer wrote that “all the very highly scented soaps” were always scented cold to avoid losing the volatile oils. You’re in good company with the masters of old. Happy soap perfuming!

Sources: Historical soap perfuming techniques and recipes are drawn from G.W. Septimus Piesse’s The Art of Perfumery (1857), which details cold added scents and small-scale soap milling as well as insights from traditional soapmaking practices. These vintage methods demonstrate the principles behind the modern process we implemented. Enjoy the fusion of history and craft in your naturally perfumed soaps!